There was not only a new head coach and GM but also literally a ton of new players. And if Zach Scott thought he was the only substitute schoolteacher among the lot of 2002 Sounders, the know-it-all student in the front row would soon inform him. There was at least three.

However, Scott was probably the only player/teacher whose Sounders career began by commuting 4-5 hours each way and who not only graduated from college but got married within the first two months.

“I flew back to Maui for three days, we got married, and then,” recalls Scott, “I flew back because we had a game that weekend.” All that and no pay.

Having made Brian Schmetzer’s squad through a tryout, the rookie from Gonzaga signed for the minimum. “We were getting $250 per game, if you made it onto the field,” Scott confirms.

But in the first match following his nuptials, a one-sided win over Hampton Roads, he never got off the bench.

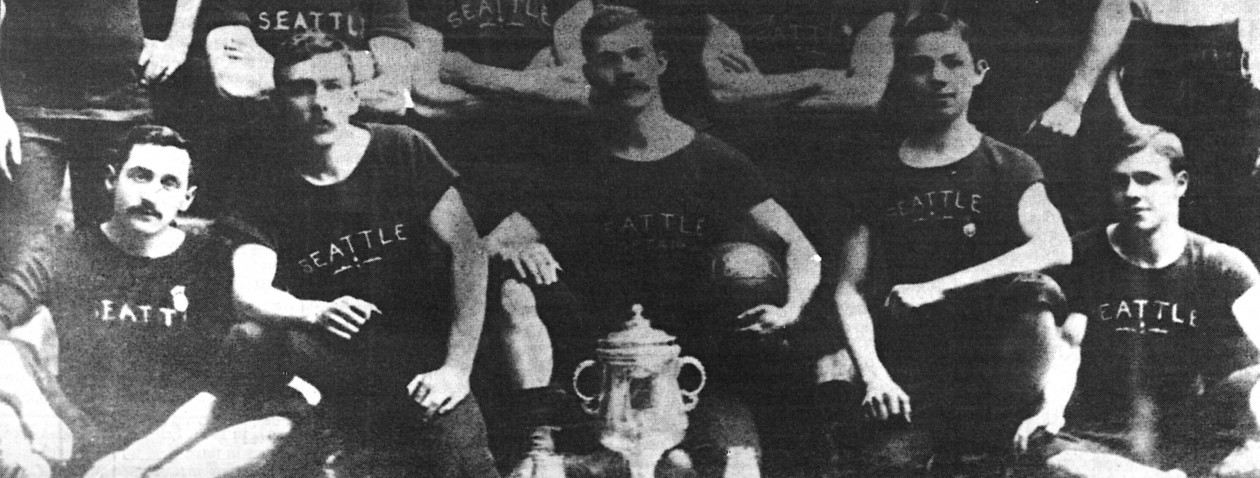

Those final years prior to Seattle joining MLS are remembered for their four trophies and two extended runs and upsets in the Open Cup. Yet as that A-League and USL era fades in the rearview mirror, some may not comprehend just how lean was the Sounders’ payroll.

Reminder: It’s A Business

It should be noted that it’s unlikely Seattle would’ve scored an MLS franchise, at least in 2007, had that USL club not existed. And it only existed because Adrian Hanauer and fellow investors kept it afloat by running a tight ship. Three pro soccer franchises in Seattle and Tacoma had drowned in red ink, and when Hanauer became the managing partner the club was coming off its worst finish for both attendance and league standing.

Austerity was one means to staunch the bleeding and at least revive hope that a Sounders club might return to the top flight for the first time since 1983. And two Sounders who would attain folk-hero status knew firsthand about an austere existence as a player.

Zach Scott and Roger Levesque are associated with some magical moments, for both the USL and MLS clubs. They are legends, and money can’t purchase that kind of status. And make no mistake, it didn’t.

Even after Scott and Levesque made the MLS roster, their wages were ridiculously low when we consider the millions made by athletes in other major U.S. team sports. Their salaries started at $40,008 that inaugural season of Sounders FC. Although they received incremental raises, the MLS Players Association pegged Levesque’s guaranteed compensation at $44,000 when he retired in 2012. Scott went on to make a Seattle record 353 appearances through 2016, when his salary had increased to $62,500.

Low Pay…And Loving It

Of course, that pales when measured against the traditional big four. The current minimum salary in the NFL is $495,000 while the NHL is $700,000. NBA and MLB minimums are $582,000 and $563,00, respectively. It’s entirely possible that the combined career wages of Levesque and Scott would fall short of those annual figures.

“With this new CBA for MLS, I hope it means things are changing, and players will get what they deserve,” states Scott. “Soccer in America may never be football, basketball, baseball or hockey, but it’s on a trajectory of growth.”

“We loved showing up to training every day and playing and playing together, and we were beating MLS teams in the Open Cup,” adds Levesque. “It was great. I look at it now, from my perspective, and I wouldn’t trade my path at all, even though there were bumps along the road and challenges to overcome.”

The first challenge for Scott was just finding a place to live affordably in greater Seattle. In all, Scott appeared in 21 matches across all competitions in his first year. That would equate to $5,250 over five months. To secure their first apartment in West Seattle, newlyweds Zach and Alana Scott needed the bride’s father to co-sign the lease.

Finding the Second Gig

Levesque arrived a year later, first on loan from San Jose and eventually a full-fledged Sounder. He had torn his ACL and his path back to MLS would be through Seattle, although probably not as he first envisioned.

“I was thrilled to still have a chance to work my way back,” he says.

Years before the term “gig economy” took hold, it was being practiced by American soccer pros, and particularly USL personnel. Sounders coach Brian Schmetzer still operated his construction business. Like Scott, Viet Nguyen and Ryan Edwards were substitute teaching. Top scorer Brian Ching, who would one day develop into a stalwart of the national team and Houston Dynamo, spent his days in the accounting office at Hanauer’s Pacific Coast Feather Co. A couple cubicles away, Scott was punching keys for data entry and accounts receivable. If a last-minute teaching opportunity or a team training session arose, his bosses (ultimately Hanauer) were understanding.

“I had no qualms about signing that contract. I knew it was little, and I would have to do other things to supplement my income,” Scott explains. “But I was still getting paid to play soccer.”

Early on, Levesque went blue-collar, along with Kevin Sakuda and Marco Velez, working at Schmetzer construction sites. As years went by, he began coaching more and taking an administrative role in a friend’s fishing business.

Constantly Reevaluating

“In the USL days, it wasn’t about huge dollars, and there was always going to be something next,” he says. “I loved to play and the team, the ownership. Because the team was so special, I wasn’t ready to move on, to give it up.”

Not everyone held on as long. Others, feeling their career path had reached its apex, opted out. Each offseason, Levesque and Scott would reassess their predicament with respect to soccer and whether it was time to move on.

Alana and Zach, and then their kids, would continually ask themselves if it still made sense, were they making it financially and, was it right for their family? When, after becoming entrenched as a starter, he approached leadership about a raise, it became obvious that while these relationships could appear familial, the bottom line was that it was a business, first and foremost. And when the MLS CBA was debated in 2015, union leaders, at times, seemed oblivious.

“A lot of guys making six figures would tell the guys just scraping by to just stand strong, because if we don’t like what the league is offering, we can go on strike,” Scott remembers. “When you’re living paycheck to paycheck, that’s not really something you want to hear.”

Playing Catchup

Of course, winning cures many ills, and by 2007 came confirmation that MLS was coming. That brought with it uncertainty: would a USL team be operated in 2008 and would they have any shot at making the MLS squad.

If either answer had been negative, that might have been the end. However, they did play in ’08 and onward. Levesque leaves several illustrious scenes imprinted on our memories: scoring the decisive second goal in the 2009 Open Cup final, and celebrations of goals versus Portland away and New York at home. After 14 years, Scott’s sendoff in 2016, with his family at his side, was a sight to behold.

Today, both are professionals in the real world, which comes with its own set of ups and downs, challenges and successes. But the chaotic existence of running from one job to the next to make the soccer life work is now a past chapter. Their college classmates obviously got a headstart in this second phase.

Levesque looks at his Stanford peers who entered the workforce in 2002, and although he has since earned a master’s degree in business, “I’m playing catchup, to some extent. My path has taken a bit longer to get here than it would’ve,” he admits.

“But I wouldn’t trade the experiences I had from playing soccer,” maintains Levesque. “Playing for an MLS team was a dream come true, and I was hugely content in Seattle and playing at a high level. I wasn’t a regular by any means, but I had my moments.”

Thanks for reading along. If you enjoyed this content, perhaps you will consider supporting initiatives to bring more of our state’s soccer history to life by donating to Washington State Legends of Soccer, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to celebrating Washington’s soccer past and preserving its future.