Professional sports is generally depicted as glamorous, a high life where players mix with other celebrities, relax at exotic and exclusive destinations and, all and all, lead a jet-set existence.

Truth be told, the majority of those being paid to perform in the athletic arena are relatively simple folk who face many of the same struggles of the common human. And while the rock star may flash a Rolex and rumble off in a Lamborghini, the stories told by the rank and file are interesting in their own right and, without question, more relatable.

Take the fishing story of Roger Levesque. Our smiling, swashbuckling former Sounder forward is well-known for his pirate face and his scuba celebration. But how many know that Levesque made his pro soccer life possible by fishing the open sea?

For over 12 years, Levesque held a commercial fishing license, working out of ports such as Astoria, Westport and Bellingham. Out into the Pacific they’d sail in search of sablefish, a.k.a. black cod. When the USL Sounders season ended, he would go out to sea where the catch enabled him to make ends meet.

“I couldn’t buy a house or condo, and it was a huge investment at the time,” explains Levesque, who took out a line of credit to pay $90,000 for the license in 2006. “It helped bridge the gap.”

Stormy Weather

In October, the weather can contribute to rough seas, and Levesque and the crew would usually stay out 2-3 days until they reached their limit. At times, it could take a week. They might sleep for a couple hours as the lines soaked, but it could be 36 straight hours of demanding and sometimes dangerous work.

“When the waves are crashing over, it was exciting. The life experience part was cool, and obviously the financial piece was lucrative, even though a lot of it went back into paying the line of credit,” he shares.

From 2009-2011, the license was stowed away since the MLS season extended beyond the sablefish season. Yet in 2012, when Levesque retired in midsummer, his next move, before starting graduate school, was to resume fishing. He continued going out through 2018, when he reached the harbor one final time. Like soccer, he knew he wouldn’t fish commercially forever.

Bonuses Could Backfire

Bonuses, in theory, present a win-win formula for an industry struggling to play on. When the club succeeds, players would profit. In theory.

However, there are tales of tightwad teams and owners exerting influence on coaches with a mind to lessen the financial burden on the club. A player might be approaching a goal total that would trigger a bonus, and the coach may sit him for the final half-hour against a weak opponent. Or a player might sit for much, much longer.

An anonymous source spoke of a friend playing for one of the A-League’s have-nots. It was a U.S. National Team regular, who would go back and forth for call-ins throughout the season in question. There was an appearance clause, and when it appeared likely he would qualify for the bonus, the coach benched him until it was no longer possible, sacrificing points for a few bucks.

Have Trophy, Will Negotiate

When Peter Hattrup signed his Sounders contract in 1994, his father, an attorney, came along to serve as his agent. Inserted into the contract were clauses for bonus-triggering achievements, such as making the A-League all-star game or postseason all-league. There was also a bonus for being named MVP.

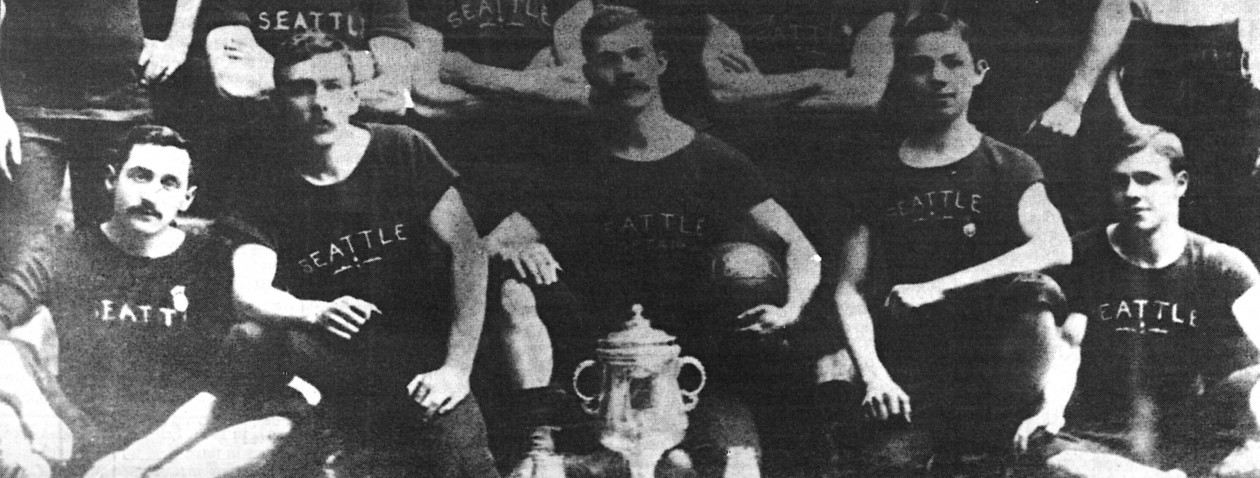

Hattrup was unquestionably the A-League’s most creative force in 1995, when Seattle surged to the championship. He scored 13 goals and assisted on 10 more across all competitions to make first team all-league and MVP. Ownership, however, neglected to pay his bonuses.

A year later, with Hattrup playing for Tampa Bay in MLS, A-League officials were hunting for the trophy, crafted in 1900 by a London silversmith. It had been intended to be a perpetual award. Hattrup still held it and told a Sounders representative he would gladly return it when his bonus check arrived. He never heard from them again.

“Honestly, I’d rather have the trophy, because that money would now be long gone and probably spent on something useless,” insists Hattrup.

Say Goodbye to Stock Options

When Chance Fry suffered a broken leg in 1996, he wasn’t able to coach youth or work on his feet in any capacity for an extended period. So, fry visited the office of a temp service, and they found him a warehouse position with Microsoft. At the time, the software giant had 3,000 employees – a tiny fraction of today’s 144,000.

“My boss liked me, and I ended up in sales administration in corporate and got a few shares of stock,” Fry recounts. His leg healed sufficiently to resume play the next year. So, what did the then 32-year-old striker do?

“I said, See ya later! I’m going back to play again,” laughs Fry. Sometimes I think, Wow, maybe I should’ve stayed there. It’s funny, I think.”

Within a year he called time on his career, unable to find his pre-injury form as goal scorer. He embarked on a coaching tract, and by 2001 was named the first head coach for the Sounders Women. There, he wanted players to get at least a taste of the finer touches he had experienced during his 15 years as a pro.

“I set-up chairs in the locker room, folded their kit all nice and put brand new shoes next to their chairs,” says Fry. “There were girls who had played college, some had even played in Germany. It was super simple on my part, but when they came into the locker room, they were freaking out; they had never been treated like that, and they thought it was so great.”

Let’s Make a Deal

In 1986, Jeff Stock determined that business, not soccer, was his future. Still, the former Sounders left back and seven-year veteran of the NASL and MISL loved the game, and his experience could benefit the next generation then advancing through the youth ranks. The convergence of all these truths came forth in his discussions with FC Seattle owner Bud Greer.

Stock was keen to transition from selling real estate to investing in properties. The Storm needed a coach for their Tacoma entry in the City League, and the senior team’s backline could benefit from his steady play and poised leadership.

“Bud offered me like $25,000, to both coach and play,” Stock recalls. “I countered by saying, instead of paying me, could you loan me $250,000, and I’ll work off the interest.”

Greer agreed, and Stock bought his first commercial property. He later bought (and sold) Wild Waves amusement park in Federal Way and now owns Caffe D’arte, a local coffee roastery with multiple Northwest cafes.

“To this day, I don’t remember knowing what the other guys were getting, and until now, I don’t think anyone else knows this story,” Stock divulges. “But that’s what got me started in business.”

Thanks for reading along. If you enjoyed this content, perhaps you will consider supporting initiatives to bring more of our state’s soccer history to life by donating to Washington State Legends of Soccer, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to celebrating Washington’s soccer past and preserving its future.