What if Seattle’s initial MLS bid had been successful in securing a charter team? And how would that bizarro world script play out?

First the Bad News

Alan Rothenberg no doubt had a lot on his mind. There were fewer than 48 hours between this press conference and the World Cup’s opening match at Chicago’s Soldier Field. As president of U.S. Soccer and Chairman/CEO of World Cup USA, Rothenberg had a lot of balls in the air on June 15, 1994, and here he was, before the almighty FIFA brass and a hoard of international media, announcing the first wave of charter cities for Major League Soccer.

Following a slew of salutations and greetings, Rothenberg got down to the business at hand, naming names as the rebirth of top-tier American professional soccer took a giant step toward reality. He said these would be the first seven, with another three cities to be determined later, with the MLS launch two years away, instead of 1995, as first proposed.

Boston, Columbus, Los Angeles, New Jersey, New York, San Jose and Washington, D.C. Back in Seattle, a roomful of soccer and sports community leaders listened in, hoping for some kind of miracle.

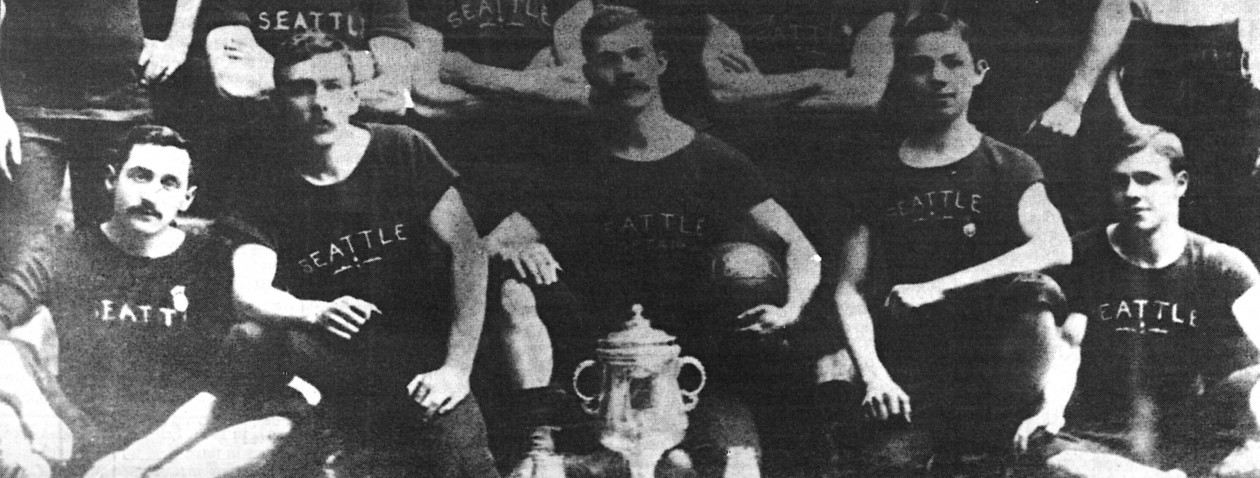

Five months before, there had been no Seattle bid committee. The lack of a suitable stadium nor a local investor/owner made the effort a non-starter. However, as so often has happened since the mid-Seventies, the Puget Sound fans spoke volumes. Over 43,000 came to the Kingdome to see a friendly between the World Cup-bound national teams of the United States and Russia.

Hank Steinbrecher, the U.S. Soccer secretary-general, was on hand in the Kingdome press box. Witnessing not only the numbers but the noise and knowledge of the throng, Steinbrecher told reporters that Seattle must submit a bid; it’s too great of a soccer city to be sitting on the sidelines. By the following week a committee formed, the state youth association fronted operating funds and despite some pushback from leadership of the budding A-League Sounders, the business of building a bid plowed forward.

Nearly 1,500 families purchased season-ticket deposits as a show of faith. Locations for potential stadiums were visited and scrutinized as were stop-gap solutions, where a Seattle team might play for the first few seasons. Rothenberg was asked if the MLS Seattle bid committee and Sounders could join forces, creating a united front and combining season ticket sales/deposits. Could these born-again Sounders be granted promotion into MLS in two years? Rothenberg’s reply: No and no.

And so, by June 15 any high hopes for Seattle becoming a charter city in MLS were waning. Rothenberg had named his seven names and, barring some breakthrough with either an owner or venue in the next few months, this bid was DOA.

But Then This Happened

But then Rothenberg suddenly placed his hand over the mic. He paused to confer with an aide and removed a folded page from the inner breast pocket of his navy blazer. Rothenberg glanced at the paper, nodded to the aide and turned back to the mic.

“I apologize; I misspoke,” he explained. “I meant to say New Jersey slash New York (or New York/New Jersey); it’s all one market. And our seventh city, giving us regional representation to the entire Pacific Northwest, America’s once and future great soccer city, Seattle is, in fact, our seventh charter team.”

It was a shocker, no matter the audience. Potential sponsors were wishing for another major market, such as Chicago, Philadelphia or Dallas (which nabbed a charter team in the second stage). But Rothenberg was advised that Seattle had no more obstacles than Columbus or other frontrunners. Besides, nationally televised soccer games always garnered high ratings in Seattle-Tacoma – and there was a track history of pro soccer support, with big crowds coming out for the NASL and now the national team. MLS would find a way to make Seattle work.

Lamar Hunt would operate the team, one of eventually four in his MLS portfolio. He would oversee Dallas and his sons would be hands-on with Columbus and Kansas City. Seattle would be managed by a Hunt-entrusted triumvirate of Al Miller, Bill Nuttall and John Best, the latter being the original NASL Sounders head coach and, later, general manager. Miller and Best had been together under Hunt at the Dallas Tornado. Nuttall was a former U.S. National Team GM. All were longtime friends and associates of Cliff McCrath, the MLS Seattle committee co-chair. Miller, incidentally, had recruited Sounders coach and president Alan Hinton from England to America when he coached the Tornado.

It’s All About the Fans

If its initial response to a bid had been relatively tepid, once MLS was a certainty, the soccer community was all-in. With TV advertisements running throughout the World Cup, season ticket deposits quickly tripled, then increased incrementally as the Sounders started A-League play, then surged to the top of the table and finally sold-out Memorial Stadium for the final regular season game. The MLS team’s business had barely plugged in a fax machine and already there were 6,500 commitments to watch a nameless team at a yet-to-be-determined location.

Over the two years leading up to the start of MLS in Seattle, there was a great deal of volatility in the market. At the newly-renovated KeyArena, the Sonics were at the height of their popularity and averaging over 60 wins per season. Down south at the Kingdome, its two tenants were troubled. In 1995, the Mariners were finally proving competitive yet there was the threat of them leaving town. After the Kingdome’s ceiling tiles began dropping, prompting the cancellation or relocation of both Sounders and Mariners games, Seahawks owner Ken Behring demanded a new stadium. When rebuffed, in early 1996 the team’s headquarters was moved to Anaheim.

As stated in the original bid package, there were multiple options for playing soccer around Puget Sound, none of them good. With two tenants already, the Kingdome was too crowded, not to mention in need of repair. The Tacoma Dome accommodated 20,000 seats and a full, FIFA-regulation field but located 30 miles south of Seattle. The University of Washington was already averse to hosting the World Cup at Husky Stadium. Hinton’s Sounders started their first season at the Tacoma Dome, then settled at Memorial, which was increasingly showing its age (49, by 1996). A proposed soccer-specific stadium in Kent was an option, but no sooner than the end of the decade.

Whereas most other MLS teams elected to play in big stadiums with greater than 50,000 capacity, Seattle leaders favored the intimacy of Memorial, augmented by investment in new bleachers and additional portable seating. Much like the original Sounders, capacity would reach 18,000 and a new artificial carpet installed, albeit only 60 (crowned) yards wide.

Branding Arrives with Thud

John Best believed the franchise would benefit from using the Sounders nickname, but once again MLS nixed it. As in the other former NASL markets, this was a new age, a new league and a fresh start was sought. Seattle’s newest team, said the league, would be known as the Voyage. Singular, cold, no alliteration and, like most of the other charter team nicknames, almost no clear association with its location. Although the vibrant green zig-zag jerseys would turn some heads (and cause static TV screens), the Seattle Voyage brand was met with a collective shrug.

The Sounders, meanwhile, won the 1995 A-League championship with a roster stocked predominantly with homegrown players. At first majority owner Scott Oki and Hinton were determined to march forward, going head-to-head with the MLS entity. However, dwindling crowds, expiring player and stadium contracts eroded their ability to leverage. When Best and Miller offered the Voyage head coaching role to Hinton several days after his team lifted the trophy, the Sounders’ fate was sealed.

In the allocation of MLS-signed foreign talent and U.S. National Team members, Hinton swooped for two of his former players at the Tacoma Stars, Preki and Roy Wegerle. He also targeted signing Everett’s returning son, Chris Henderson and young Vancouver super striker Domenic Mobilio. He drafted or bought-out the contracts of 10 Sounders, including A-League MVP Peter Hattrup and goalkeeper of the year Marcus Hahnemann. Hinton reasoned that playing at home, before family and friends, local lads could strengthen the connection with fans and instantly create a continuity no other team could claim.

It may not have been much in the way of a marquee-name squad, but they played as one and, bolstered by international acquisitions from the league, Seattle Voyage finished runner-up to Tampa Bay during the inaugural regular season before being eliminated by LA in the semifinals.

Attendance, while limited by capacity, was impressive at just under 18,000. Season-ticket renewals for 1997 ran about 75 percent. However, walk-ups and continued on-field success helped bridge the gap. While Seattle crowds dipped, it was far less than the league average slide of 2,800 in the second season.

A Place to Call Home

Of greater consequence than any given match in 1997 was Seattle’s future in the game. Memorial Stadium lacked the magical atmosphere of the Sounders’ Camelot era, when fans and players held fewer or more modest expectations. It was cramped, just as much for players as crowds.

Construction had begun on a new Mariners stadium, and prospective Seahawks owner/savior Paul Allen was proposing that the Kingdome be demolished, and a football shrine erected in its place. When polling indicated the statewide proposition was in jeopardy, Hunt got on board, insisting this would also become the new home of MLS. Thanks to the soccer vote the measure passed, barely.

Midway through 2002, the Voyage moved from Memorial to Seahawks Stadium, and it came none too soon. The team remained competitive (after all eight teams always made the playoffs), but had the stadium dilemma remained, Seattle might have been one of the two contracted teams, instead of Tampa Bay or Miami. Hinton was retired, as were most of the players he brought with him. With forgettable player names and few staying for more than a couple seasons, the bloom of MLS had withered.

attendance to near 20,000, with nearly 30,000 for the inaugural match. Preki, at age 40, benefitted from greater operating room, and Henderson still exhibited the engine of a player 10 years younger. The one true drawback: Allen decided that instead of grass, the stadium playing floor would be artificial.

Hunt began listening to offers for two of his MLS holdings, including Seattle. The threatened exodus of both the Mariners and Seahawks had made fans of teams wary of out-of-state owners. Allen, more focused on reshaping the Seahawks’ image, wasn’t interested. Among locals, most were only open to becoming a partner. Investment groups began bargaining with Hunt. In 2005 he sold the Voyage to a group of California investors for $11M, just above the Salt Lake and Toronto’s expansion fees.

How to Bring Back the Buzz

Crowd support, once the new stadium buzz subsided, leveled off around 17,000, still respectable and among the MLS top five. The crowds, which were largely families in the first seven seasons, were morphing, with more millennials. A drum-banging bunch began growing in the southeast corner. Although Seattle continued to make the playoffs year after year, there were no trophies and there’s a sense of general impatience with the bland (they were now wearing all-white home kit with green trim) brand that was the Voyage.

In 2005, owners of the USL Tacoma Tugs, used their connections to bring Real Madrid to Qwest Field, to play the Voyage in a friendly. It was the first major international tour to stop (Manchester United opted for Vancouver in 2003), and the turnout of 55,000 indicated there was an untapped audience that didn’t fancy MLS.

One of the Tacoma owners, Adrian Hanauer, initiated conversations with Seahawks president Tod Leiweke and VP Gary Wright. All three shared a passion for soccer and a vision for what pro soccer could once again become in Puget Sound. The Voyage ownership group wasn’t interested in advice on the business front. They reminded the community that fans should support their endeavor because ticket prices were reasonable, the team regularly qualified for the playoffs and would soon play in Superliga, the new competition featuring MLS versus LigaMX clubs. Furthermore, they were exploring the signing of a first Designated Player in 2008.

At that point, the Great Recession applied the brakes to all MLS expansion plans. Hollywood exec Joe Roth’s proposed Vancouver start date was pushed back to no sooner than 2012. Voyage owners wanted out; their investment portfolio had cratered. Hanauer cobbled together a group to buy a majority stake for $16M. Among the partners was Paul Allen’s Vulcan Sports, which would now manage the business side. They soon recommended a rebrand. The Californians had rejected such suggestions and the Sounders name in particular, claiming that brand was ancient history and would no longer resonate with fans who were in their youth back in the NASL and A-League days.

Yet in 2009, the Voyage came to an end; the Sounders re-emerged. Hanauer was unsuccessful in prying Sigi Schmid loose from Columbus, but he hired Paul Mariner and convinced him to bring aboard Brian Schmetzer, the Tacoma coach, as the top assistant and Chris Henderson as technical director. Local hero Kasey Keller, after solid career in Europe, was signed to a two-year deal. Leiweke claimed it all to be a reboot, an unshackling from MLS 1.0. There was now a vision of reaching the crowd levels of the NASL days and a more vibrant, loud stadium atmosphere.

The reborn Sounders did not make the 2010 playoffs, yet led the league attendance at just over 23,000. It had taken 14 years, an ownership change, a new vision, but Seattle and MLS – now with David Beckham added – seemed to start the new decade on an ambitious trajectory. Once Roth’s Vancouver comes online, Cascadia might produce a combustible rivalry, one that Portland might someday join. Practically everything was falling into place: local ownership, front office expertise, a likeable brand, a major-league stadium and the prospect of local rivalries.

If only all that had been the case in 1996. Timing, it proved, can be everything.