If there is to be a monument celebrating John Rowlands, it must stand tall and strong. It must exude tenacity, cunning and somehow exhibit a pinch of mischief.

For John Rowlands must be known for far more than just the goal that sounded our soccer community’s collective awakening. He was a buoyant, forceful personality; someone who would lead you headlong into the fray yet elicit some hardy laughs along the way. He was adventurous, striking out from his homeland for this faraway port to play for a side that had no prior existence. Here he would join, and in many ways lead, likeminded lads who blazed a path for what has become a thriving, footballing realm. He was a beacon.

John Rowlands, who led the line and, in many ways set the carefree tone of those first Sounders teams of the Seventies, has died, a victim of Coronavirus earlier this month in his native northwest England. He was 73.

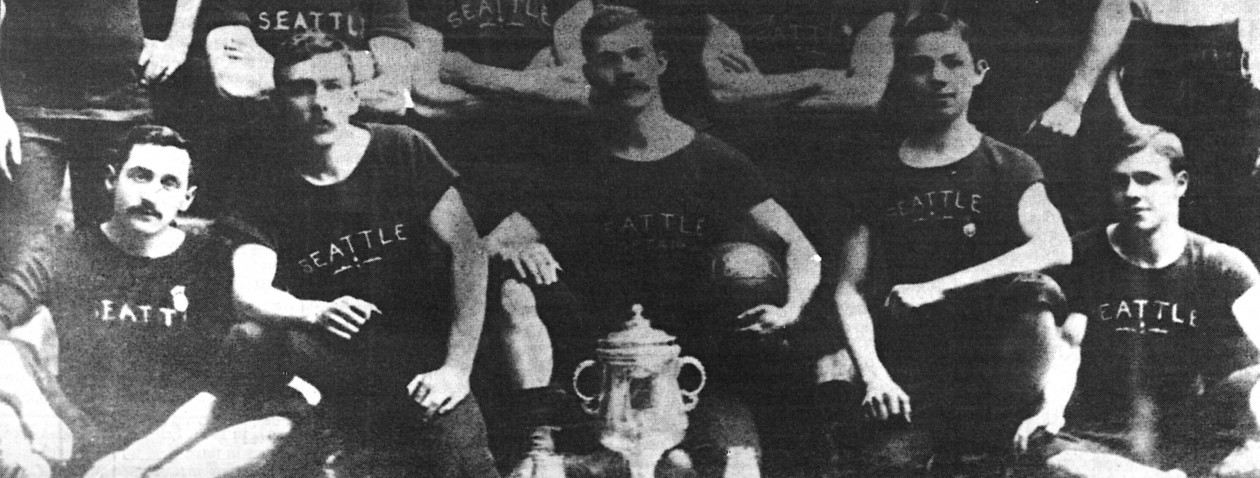

Yet to the vast majority of contemporary footy followers around Seattle, the name Rowlands may fail to resonate. You might find a fuzzy image of him on YouTube or the black and white photographs such as those on this page. However, that’s all two-dimensional, and if one really wants to identify themselves a Sounder for life, let’s learn a bit about the late, great Sounder, John Rowlands.

Once John Best got a look at the narrow, crowned and unforgivingly hard Astroturf of Memorial Stadium, Seattle’s first coach envisioned the cast best equipped to win games in those cozy confines while at the same time winning fans. The plan: Those first Sounders would go direct, straight down the middle.

Looking for a Lighthouse

“If I could find a lighthouse to be the front striker,” Best told me in 2014, “then we can play it in the air. So, we found John Rowlands, who was very good in the air.” Best, like Rowlands, a Liverpool native, had gone shopping for a classic No. 9 in the Fourth Division. Specifically, he was watching a struggling side called Crewe Alexandra. Rowlands scored just a single goal for Crewe, but his productivity at his previous stop, Workington, was encouraging.

Claudia Best remembers how excited her husband was to find and sign Rowlands. “John (Best) felt John Rowlands was the perfect center forward for a team that would be introducing soccer to the American audience,” recalled Claudia. “He knew they would love his flamboyance and his toughness and his ability to score goals. He was a very important part of the first Sounders team.”

By then, at age 27, Rowlands had bounced around, always in the lower tiers, where supporters were passionate, but often negative and few in number. Whatever Best told him about Seattle and traveling throughout America during the English offseason must have been beyond tempting, for by the first of May 1974, Rowlands – plus Crewe teammates David Gillett and Alan Stephens – arrived to join the Sounders on loan.

Housed in an apartment together, with Willie Penman, they decided soon after landing to visit Pike Place Market. They walked three miles each way, from near Queen Anne Bowl. It was a sunny spring day, and they liked what they saw. A fishmonger, detecting their British accents, suspected they were with the new team in town. Within a couple more weeks, each of them would become widely recognizable, and none more so than Rowlands.

An Auspicious Introduction

Bob Robertson introduced us. Robertson, the original voice of the Sounders, was adept at providing a pithy description of characters to his audience. And from his vantagepoint that Cinco de Mayo in East L.A. College Stadium, his first husky-voiced goal call was reserved for Rowlands. It was Rowlands who would rise to meet the Pepe Fernandez cross and head home for the club’s first-ever goal five minutes before halftime.

A week later, on Mothers’ Day, Rowlands was there in flesh, for all the fans to see. He was instantly tagged as Big John. Admittedly, he stood a fraction under 6-foot-1. But it was all relative; only two other regulars scaled 6 feet or above. Rowlands played much bigger, using his sinewy strength and broad shoulders to gain and hold position, plus he had hops. Rowlands could climb the ladder to win high balls and redirect them to teammates or, more forcefully, past goalkeepers.

In that inaugural match at Memorial, Rowlands played gigantic. After Penman’s opener, he hears the roar himself as his header nestles in the net against Denver. In the 34th minute, in a rare floor show for Rowlands, he beats Mick Hoban and keeper Mick Poole (both future Timbers, incidentally), first on the dribble, then with the left foot pass into the empty cage.

By the third match, and another brace, Rowlands was rolling like never before. The Sounders were flying high and tickets were a hot commodity. TV and newspaper interviews and standing ovations from more than 12,000 strong. It was a far cry from playing in mud before gatherings of 2-3,000 back home. John Rowlands was the Sounders’ first star, much the same way Fredy Montero burst upon the scene 35 years later.

Not Artistic, But Acceptable

Seattle Times columnist Georg Meyers was fixated on his head, which delivered four of those first five goals. Sometimes the ball would occasionally carom off his ear, nose (broken four times) or eye. “Now and again you bang one in off the ear,” Rowlands said. “It’s not artistic, but it’s acceptable.” Making things happen with his head, he added, is “the thing I do best.”

In the pre-Pelé days of the NASL, Rowlands was a dominating force. He was voted first team all-league after scoring 10 goals and also leading the team with eight assists.

Beyond his prowess in Seattle’s direct style that first season, Rowlands was also the enforcer. That role became more apparent in the second season, as fans became more educated and watched off-the-ball activities and TV cameras, both the weekly coaches’ show and live transmissions, would isolate his play.

In his two Seattle seasons, Rowlands totaled 20 goals and 13 assists, reaching the former plateau faster in than all but three others in the top-flight. Beyond the glory, he furthermore did much of the gritty work.

He Walked the Line

Rowlands accumulated 180 fouls in those first 40 matches, an average of 4.5 per match. No other Sounder was within 100 of that sum. Still, he escaped ’74 without a single card. In ’75 he saw three yellows and one red, for backhanding a Dallas defender directly in the face. Noted Best: “John’s a veteran. He knows how far he can go before crossing over the line. He’s been walking that line most of his life.”

“I am the most marked man on the field, played the tightest,” explained Rowlands. “Obviously, I’m involved in more contact. And a fellow likes to give as good as he gets.”

When Sports Illustrated first staffed a Sounders-Timbers encounter, Rowlands featured prominently. The young rivalry had quickly risen to a boil in Portland, with 45 fouls whistled in the Timbers’ 2-1 win a week earlier. In Seattle, SI’s Pat Putnam watched as an exchange of goals soon escalated to an exchange of armlocks, then blows.

“Fights began breaking out all over, most of them involving Seattle’s John Rowlands, a free spirit who is both the Sounders’ target man and their enforcer,” wrote Putnam. At one point near the end of the first half there was a collective gasp of the capacity crowd as all eyes fell on Rowlands.

Portland pumped a high ball into the penalty box where Rowlands, already on a yellow, was marking Timbers center back Graham Day. Both players fell to the ground, although Day’s descent was plainly made possible by Rowlands haaving both hands around his neck. If it was a mugging, referee John Davies didn’t see it. Rowlands later cheekily told Putnam: “I thought it was a great piece of defensive work myself.”

Still on the pitch an hour later, Rowlands rises first to a long throw-in and flicks it far post for the winner, 3-2, three minutes into overtime. Scribbled Putnam: “Never have 17,925 fans made so much noise.”

‘Owe You A Lot, Big Man’

In his book Circle of Life: 1968-2019, former Seattle captain Adrian Webster described Rowlands as an “in-your-face” competitor who backed down to no one, who could intimidate a foe, whether in training or play, then cheerfully smile or wink to a knowing teammate.

Gillett trained, played and, for a time, lived with Rowlands. “A good target man who was as aggressive as hell, especially in the box, where it counts,” said Gillett. “The perfect man to excite the new fans, awesome in the dressing room and just a great character off the field.”

There are stories of the Crewe days, when after training Rowlands would sell teammates various goods – from sweaters and socks to cutlery, cookware and watches – all from the trunk of his car.

“The Big Man had a dry sense of humor,” observed David Butler, who played wide or underneath Rowlands in the attack. “Davey Butler knows he would not have scored those (14) goals at Memorial Stadium if not for John’s tenacity with defenders. I owe you a lot, Big Man.”

Fresh Flowers and The Vicar

Geoff Wall, a fixture in the Seattle soccer scene long before the Sounders’ arrival and a friend to many of those original players, has no shortage of Rowlands stories to share.

“One time, John had upset my wife, and after a few days he came by the house to apologize and give her a bunch of flowers,” Wall said, “but he had picked them out of my garden!”

Before or after Before or after training at Memorial, Wall continued, Rowlands would sometimes disappear from the field or locker room. Wall later learned he had slipped into the stadium custodian’s office to make long-distance calls back to England, free of charge.

Although the Sounders, partly owned by the Nordstroms, issued blazers and dress slacks to wear on road trips and formal appearances, Rowlands rebelled. He chose less formal wear, giving Wall the clothes.

Wall doubled as an undercard boxer in the Sixties, and that no doubt gave him instant cache´ with Rowlands, who loved boxing and horse racing, perhaps more than football.

Cliff McCrath, who was a scout and consultant for the Sounders, tells the tale of the 1974 season-ending banquet hosted by the owners. Rowlands, who would have been the headliner, arrives late. Very late. In fact, he misses both the meal and the program. Asked why he was late, Rowlands replies, “I was over in Bainbridge (Island), helping the vicar with worship.” Knowingly, his teammates and McCrath laughed so hard they were in tears. In truth, before flying back to Britain Rowlands had made one last trip to the local horse track, Longacres.

While Rowlands and the Sounders dealt the Timbers a defeat that night, Portland went on to win the division and homefield advantage in the playoffs. A record crowd of 31,523 awaited Seattle at Civic Stadium 10 days later. Rowlands shushed the throng shortly after intermission, sending the visitors in front by nodding home a Paul Crossley cross. But it was Portland’s night to celebrate. The Timbers tied it, then won it in the seventh minute of overtime, setting-off a massive pitch invasion.

Journeyman Journeys On

That happened to be the end of an era. Home games moved from cramped quarters of Memorial to the humongous new Kingdome. Consequently, the squad was retooled. The larger dimensions of the new pitch would require greater sophistication. Best and GM Jack Daley, who rarely hesitated moving players, even popular ones, declined to bring back five starters, Rowlands among them.

“John obviously was a good striker, but he did most of it with his head,” reasoned Daley. To begin the new era, Best recruited a new striker, England World Cup hero Geoff Hurst. Noted Daley, “Hurst has the footwork; he can kick with either foot, and a bigger field demands more complete players.”

While back in England playing for Hartlepool during the winter, Rowlands received notification the he had been traded to San Jose. His Sounders days, perhaps his most glorious days, were done. The Earthquakes converted him to a central defender, the position he would play for his final five NASL seasons. His first trip back to Seattle was brief and painful; he departed after 12 minutes with a fractured cheekbone.

In all, Rowlands played for 13 clubs over 13 seasons. He was a journeyman. None got more offensive production than Seattle, where he scored in both his first and last appearance. Beyond that, Big John made impressions. Kids all over Puget Sound would reenact his headers in their backyards and wearing ’18’ was fashionable.

Trusty Oak Remembered

In 1982, when Best was general manager, he wanted desperately to rekindle the connection between the club and its fans. He organized a reunion game, bringing back 12 of his players from those Memorial years. Seven of them were flown-in from England, including Rowlands. A public reception was held at the Center House on the eve of the reunion game, played against mostly ex-Whitecaps, prior to the Seattle-Vancouver main event.

It was evident the Sounders fans had not forgotten their “originals.” The lines for autographs and well-wishers were lengthy. Meyers, the Times columnist, remembered Rowlands well, writing in his reunion feature, “Rowlands was the trusty oak, the craggy mate you cherish as a friend and fear as an opponent.”

Rowlands kept on playing non-league football as he transitioned to restauranteur and publican, both in America and Britain. On this side of the Atlantic he opened taverns in the Bay Area and near Orlando, where the St. Andrews Tavern is still a popular English-style pub in Altamonte Springs that has spawned an entire community of its own. His son, Nick Walker, now runs it. His daughter, Kelly Rowlands, operates Gardeners Arms in Chester, England, where his presence also remains. Rowlands played into his Fifties for a side he named The Fossils.

It seems wherever Big John lived, he was greatly loved. Earlier this week, outside the family home, his friends and admirers, gathered yet distanced, displayed Liverpool flags and touchingly sang in unison You’ll Never Walk Alone. Rowlands’s ashes will be cast on his parents’ graves and the River Mersey.

Leaving an Indelible Mark

For a player who rarely stayed with a team for more than a season or two, Rowlands made his mark. Since his death on April 14, there have been tributes by a number of those minnow clubs, from Workington to Barrow to Stockport. News traveled fast via the St. Andrews Facebook page.

Some reminisce about the immediate impression he made, for his earnest work ethic; “more skill than he was credited” and “never prolific, but always reliable.”

From his friends and teammates in Seattle: “A good friend and scoundrel,” wrote Wall. “He ate all my food, would not clean-up, and I had to move out, but I liked him a lot; I loved knowing him,” offered Gillett. Said Pepe Fernandez: “He was tough. He was to be very respected, but after the game he was a gentleman,” adding, wistfully, “We got along, the whole gang back then. This kind of news comes too often.”

In Seattle, where the phrase ‘Sounder for Life’ is often spoken, it’s only fitting to remember, to celebrate an original Sounder, our first hero, John Rowlands. Whether our lighthouse or our mighty oak, he stood tall and always will.

Thanks for reading along. If you enjoyed this content, perhaps you will consider supporting initiatives to bring more of our state’s soccer history to life by donating to Washington State Legends of Soccer, a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated to celebrating Washington’s soccer past and preserving its future.

Frank: You have long been the master of those who buy ink by the barrel, but this compelling, fast-moving tribute to Big John has vaulted you to the Maestro of Manuscript equal in talent to the guy who painted ceilings on his back! I just dropped daughter Stacey off at the airport and didn’t move an inch after checking for messages and saw your article – and, albeit parked with motor running in the No Waiting, Loading and Unloading Only Curbside Lane – I read every word of your magnificent narrative! The line will quicken – and grow in length – by we who will be desperate to change our ‘wills’ ensuring whatever is eulogy will only be penned by the Master MacScripter! To steal a phrase from Jerry Yeagley (Indiana’s legendary Hall of Famer) – DON’T YOU EVER DIE!