They were fearless from the first kick. And 45 seconds later, they began making believers of fans and foes alike.

If footy supporters around Puget Sound feared the Vancouver Whitecaps would wipe the Astroturf with the amateurs of Football Club Seattle, they were at least given pause when the local lads stormed in front in their inaugural match at Memorial Stadium.

Forty-five seconds into its challenge series versus Vancouver and two other NASL clubs, plus the U.S. Olympic Team, Bruce Raney bulged the west end netting. His former college coach, Cliff McCrath, climbed a railing and thrust his first in the air as fans, some yet to find their seats, screamed in delight.

Off and Running

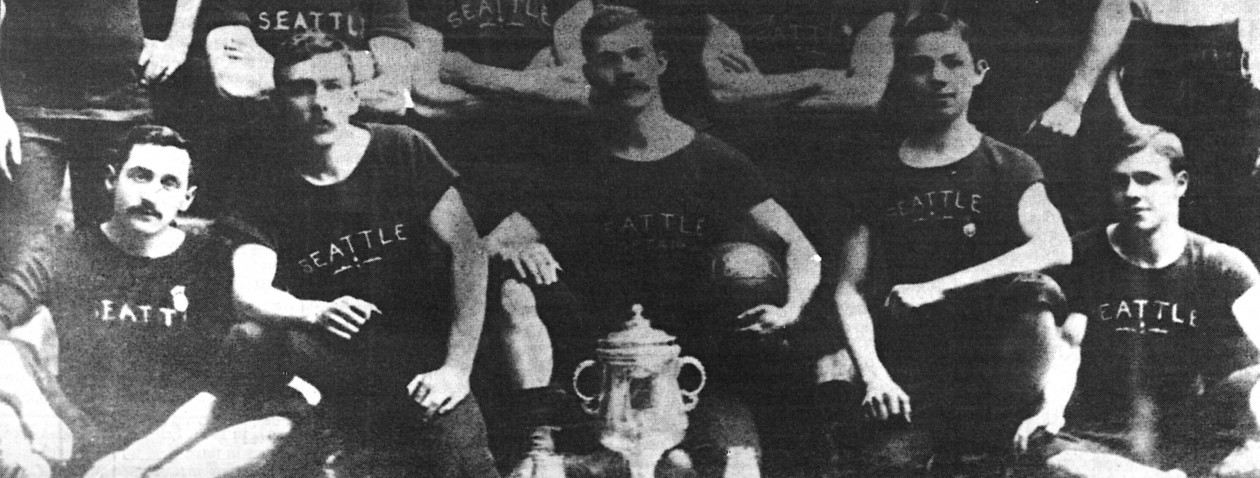

FC Seattle was off and running. A win would come, and crowds would grow, albeit modestly, before that first season was finished. Soon after, a feeder system and league play, and a senior women’s team would be launched. Big name players would arrive, two overseas trips taken, and a trophy would be lifted.

Yet it was that belief may have been the biggest biproduct and most enduring legacy.

Continue reading FC Seattle, 40 Years On – Part 2: Seattle’s Sons